THE DURAND GROUP

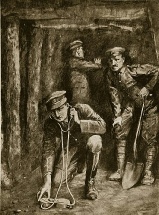

Underground Working Parties

Typically there would be 4 tunnellers working at the face (one of whom would be resting), plus 2 tunnellers mates handling trolley, air pumping and preparation of timber. Generally infantry working parties were employed to remove the spoil from the shaft heads and dispose of it. (One foot run of subway created 70 sandbags of spoil). At any time a Tunnelling Coy would have several digging parties working towards each other. A common pattern was that in each Section three of the four shifts would be in line, each for 4 days, and one shift resting or on light duties out of line for 4 days. Shifts normally worked underground for 8 hours in every 24 hours. The 16 hours ‘off’ included moving into and out of the line.

Tunnel Construction

This was influenced by many factors. As a rule of thumb a Tunnelling Coy would drive a subway, including side chambers, at about 20ft (6m) per day. Rates over double this were achieved on occasion. The British miners tried to strike a balance between sufficient space to work efficiently and minimizing the spoil to be removed. Fighting tunnels were generally between 4ft 6 ins and 5ft 2 ins high (1.4m to 1.6m) and 2 ft 6 ins to 3 ft wide (0.8m to 0.9m). There were though many variations depending on circumstances and tunnelling companies. For example the New Zealand Tunnelling Company preferred more head room. It was rare to construct crawl only tunnels, though sometimes in emergency (usually in clay) the miners would burrow what they termed ‘rabbit holes’. French miners tended to smaller tunnels than the British. Dimensions of German tunnels were similar or slightly larger than the British.

British practice was to use no more support than essential. In clay this did entail extensive timbering but in chalk, supports were only used at weak points or in fractured ground close to mine blows. In Flanders, where deep tunnels were driven through ‘Blue Lias’ (a form of clay) it was sometimes necessary to use steel girders to resist expansion pressure. German practice was to ‘close timber’ most tunnels regardless of support requirements, a procedure that slowed down their progress. When silent digging the chalk face was softened with water before pieces were prised out with a spike. This was a very slow process and rarely used.

Locating Enemy Tunnels

Ground is a good conductor of sound so by listening to sounds of enemy working and then taking compass fixes from several underground positions and obtaining an intersection it is possible to locate enemy activity. The most effective instrument for this was a French device known as a geophone. This comprised two pressure sensitive diaphragms with a tube leading from each to the ear of the listener. These would be moved until equal pitch was obtained in each ear. A bearing taken at right angles to the line between the two diaphragms would show the direction of the sound. Listeners (usually officers or Senior NCOs) were selected for their near perfect aural capability and trained for about six weeks at a special ‘listening school’. The procedure was remarkably accurate, and experts could even use it to determine differences of elevation. Numerous methods were employed by both sides to confuse or mislead the other, or to draw the opposing miners into an underground ambush. Listeners were involved in a very deadly game of bluff.

Explosives Guncotton and gunpowder was used in the early mines. However from early 1915 the British employed ammonal. This is a compound of 65% ammonium nitrate, 15% TNT, 17% coarse aluminium and 3% charcoal. It is an inert slow lifting explosive. To explode it has to be ‘hit’ by a powerful detonation wave, usually provided by guncotton primers. These in turn have to be initiated by detonators containing highly sensitive fulminate of mercury. Firing was usually with an electrical circuit. For some very large mines gelignite boosters were used. Ammonal was normally decanted from 50 lb tins into 25 lb rubberised bags clamped with wooden slats. Most of the ammonal found in the Vimy tunnels by the Durand Group is still in near prime Condition.

Intensity

In June 1916 (the peak month), along the line of the British front, the British fired 101 mines or camouflets; the Germans fired 126; a total of 227 in the month. This equals one mine every three hours.

All materiel on this site (except where indicated) is © Durand Group 2023